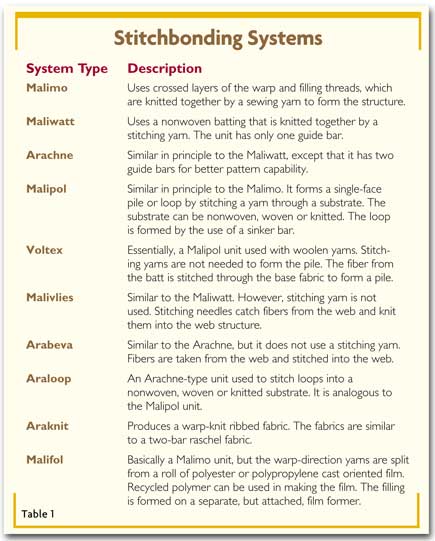

By Richard G. Mansfield, Technical Editor Textiles In StitchesStitchbonding is finding its niche after years of trial and error. Stitchbonding is a hybrid technology using elements of nonwoven, sewing and knitting processes to produce a wide range of fabrics that are used in home furnishings and industrial fabrics, including composite structural applications. The versatility of stitchbonding can best be understood by reviewing the types of stitchbonding processes (See Table 1).The initial work on stitchbonding took place in Czechoslovakia and East Germany during the 1960s using short-staple fibers to produce fabrics for industrial and utilitarian non-styled household uses. These fabrics were made using creel-fed, spun stitching yarns. As the use of stitchbonding spread to the United Kingdom and other countries, nylon and polyester filament yarns became the preferred materials for the stitching component. Malimo Stitchbonding SystemsThe Mali system of stitchbonding was initiated during the late 1940s by Heinrich Mauersberger of East Germany. His U.S. Patent #2,890,579 was issued on June 16, 1959. Mauersbergers first fabrics were based on joining warp and filling yarns with a stitching yarn to produce a woven-like fabric. The first product produced by the Malimo stitchbonding process was a toweling, made in 1952. To introduce the Malimo machine in the United States, the East German manufacturer appointed Klauss Bahlo to be its manufacturers representative in the United States. When CromptonandKnowles Co. took a license from the East German manufacturer of the Malimo around 1962, Bahlo became a vice president with the company. CromptonandKnowles imported a number of machines to the United States.

Karl Mayer’s Malimo machine is used for the stitchbonding of multi-layer reinforcement fabrics for the composite industry. The first two Malimo units went to Guilford Woolen Mills in Guilford, Maine. Guilford was then run by King Cummings. The companys initial efforts with the Malimo machine were concerned with the use of woolen yarn. By mid-1963, Cummings decided to sell development time on the companys Malimo machines to other textile companies, rather than trying to develop fabrics for Guilford. Indian Head Co. became interested in the Malimo machine and ran extensive trials on the machinery at Guilford. Indian Heads decision to put the Malimo in a knitting plant was based on its experience gained from using the machines at Guilford.In March 1963, Indian Head ordered two Malimo units at a price of $45,000 per machine. Four months later, Indian Head set up the first Malimo machine at its Native Lace Co. plant in Glen Falls, N.Y. Dan Duhl, who later was to become president of the Polylok Corp., was appointed product development manager for the Malimo program in April 1964.Initial trials by Indian Head with the Malimo used a range of materials including mohair, worsted and cotton novelty yarns. A considerable number of mechanical problems were encountered with the early Malimo machines. Fabric problems included curling selvages, side-to-side nonuniformity and mending problems.As development work at Indian Head progressed with the Malimo fabrics, home furnishings fabrics were recognized as having good potential. The first production order by Indian Head was a drapery fabric using a preshrunk polyester stitching yarn combining a random warp of cotton and a filling of natural and yarn-dyed cotton and rayon. Another drapery fabric produced by Indian Head was a fabric known as Fiberglo. This fabric was made of modacrylic, rayon and polyester fibers and had excellent flame-resistant properties.A number of promising fabrics for casements, draperies, reinforced industrial fabrics and coating substrates were developed by Indian Head from the start of its program in 1963 until its termination in 1973. One of these fabrics was a cold-weather apparel fabric called Thermal-Dermal made by stitching yarn into polyurethane foam.Indian Head, as a $400-million conglomerate, did not want to absorb further losses on the Malimo program. The establishment of the Polylok Corp. by Duhl provided a good mechanism for Indian Head to terminate the project. The machinery was sold under very favorable terms to Polylok, which allowed Duhl to start a business with a relatively small initial capital outlay. Other Mills That Worked With The MalimoBurlington Industries, Greensboro, N.C., put a considerable amount of effort into the Malimo system over about a four-year period. It established a separate Nexus Division for the Malimo program, developing a number of casement and drapery fabrics. A line of tablecloths was developed and marketed through Sears and other chain stores. Burlington unsuccessfully tried to develop womens- and menswear fabrics with the Malimo. The womenswear fabrics were based on woolen spun yarns, and the menswear fabrics used worsted yarns. One of the major shortcomings of the Malimo fabrics for apparel use was their lack of recovery when deformed; garments would bag at the elbows and knees.In early 1969, Burlington announced the division was closing, and activities with the Malimo machines were terminated. Both J.P. Stevens and M. Lowenstein also were unsuccessful in their efforts to develop apparel fabrics using the Malimo machine. Reeves Brothers was interested in Malimo fabrics because of their high tear strength and dimensional stability. However, in comparing the Malimo substrates to woven fabrics for coatings, at that time it found that no cost savings were obtained with the Malimo fabrics.Libbey Manufacturing in Lewiston, Maine, under the direction of President Paul Libbey, entered the stitchbonding business in the late 1960s using Malimo and Maliwatt machines. Libbey produced Malimo casement fabrics for the home decorating trade, and industrial glove and shoe linings using Maliwatt equipment.

Why Did Malimo Have Only Limited Success In The U.S.Stitchbonded nonwovens gained acceptance in Europe, particularly in the Soviet-dominated Eastern-Bloc countries, where fabric aesthetics were not a major concern. Later, acceptance of stitchbonding grew gradually in Western Europe for specialty fabrics. By 1984, there were more than 1,000 machines producing more than a billion yards of fabric per year. Most of these machines were producing industrial fabrics.The Malimo achieved success in home furnishings and domestics in the United States, where the unique appearance of the fabrics was a virtue. Included were fabrics for casements, draperies and tablecloths. In industrial fabrics, the Malimo has been used successfully to make substrates for coated abrasives and in conveyor-belt applications in which extreme dimensional stability is important. Polylok, Tietex and Superior Fabrics were able to develop Malimo fabrics for vertical blind louvers.A major factor in the disenchantment with the Malimo was that it was oversold to the textile industry as a high-speed replacement for the loom. Raw materials for fabrics produced using the Malimo cost as much as or more than raw materials used for woven fabrics, because a three-yarn system is used and the quality of the stitching yarn is very important. Direct costs for the Malimo are higher than weaving because one worker can attend only about five machines, while a worker can attend more than 100 looms. The stitchbond machines produced in the Soviet-Bloc countries suffered from lack of quality control in their manufacture and required extensive maintenance work to keep them running Tietex Co.Tietex Co., Spartanburg, is the most successful stitchbonded nonwovens company in the United States and the worlds largest producer of stitchbonded fabrics. In addition to Malimo machines, Tietex has Liba stitchbonding machines. The company was started in 1972 by Arno Wildeman. Wildeman had been associated with Cosmopolitan Textiles of England, a producer of stitchbonded fabrics used for printed drapery and bedspreads. Wildeman developed techniques for modifying the machines he purchased to make them more reliable and versatile. One of his patented developments was a method of locking in the tricot stitching in a Maliwatt-type machine by tying in the stitching yarn to the fleece fibers.Tietex diversified its product line and soon added mattress ticking and flexographic printing. Tietex is believed to be the only major company using flexographic printing for textiles. Up to eight colors can be applied on this unit. One of the major advantages of flexographic printing is that it requires less dyestuff to produce a shade than it would to print the same pattern and shade using rotary screen printing or roller printing.The company has developed techniques for foam finishing and foam application of coatings to its stitchbonded fabrics. The foam application of finishes to prevent pilling has been an important factor in expanding the companys range of products. Tietex also has developed 44-gauge stitchbonding equipment.Tietex now has the most diversified range of products in the stitchbonding business. Home furnishings products include mattress ticking, bedspread and drapery fabrics. The development of the stitchbonded mattress ticking by Tietex virtually eliminated the osnaburg cotton ticking from the market. Expansion And Diversification By TietexAfter the sudden death of Arno Wildeman, his son Martin took over the reins of the company and continued to expand and diversify the company in accordance with his fathers long-range plans. The company has expanded its Thailand-based plant, Tietex Asia Ltd., which was built in 1997. Some of the output of the Thailand plant is sold in Asia for use in footwear, hunting and recreational products. The company now is considering building a plant in Poland in order to better serve the European market.Recently, the company has developed a line of stitchbonded upholstery fabrics. An affiliated U.S. company, Interflex Laser Engravers, Spartanburg, produces flexographic printing rollers for Tietex, as well as rollers for flexographic printing of film and other materials for the packaging industry. New Techniques For Stitchbonding

Karl Mayer’ latest machine, the Multiknit, produces fabric with a double-sided knit effect.Karl Mayer of Germany has modified the basic Malimo technology to produce three-dimensional fabrics. Using these techniques, fabrics can be produced that have low specific weight, good compressive elasticity and moldability, and possible use as polyurethane foam replacement in automotive and other seating uses.The Kunit three-dimensional fabrics made of staple fibers are comprised of one stitch side and one pile loop side that has an almost vertical fiber arrangement. The lengthwise-oriented fibrous web is folded and compacted into a pile fiber web at high speed and supported by a brush bar. The fibers are pressed into needle hooks by the brush bar to form a stitch. In the Multiknit system, a fleece fabric with plain stitches on one side that has been made by the Kunit process is used as the Multiknit base fabric. The double-sided knit effect of the Multiknit fabric is produced by forming the fibrous content of the pile folds into loops to produce the second knit surface. The Outlook For StitchbondingThe growth in stitchbonded fabrics will be relatively modest in home furnishings and more conventional types of industrial fabrics. The greatest potential will be in fabrics for composites and fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP), and in products to replace polyurethane cushioning in automotive and furniture seating. The availability of stitchbonding equipment from a high-quality and development-oriented company like Karl Mayer should also be a key factor in the growth of these newer applications.June 2002