Automation continues to assist the growth of U.S. manufacturing.

By James Borneman, Editor In Chief

A common thread in recent investments in the U.S. textile industry seems to be the effectiveness of automation and process control in making the United States a globally competitive manufacturing destination. Many announcements cite four factors driving investment in U.S. textiles — superior cotton supply chain, relatively inexpensive and dependable energy supply, highly educated labor force that can handle automation, and good transportation infrastructure including ports and roads.

The automation and textile industries have much in common in that each is widely misunderstood and undervalued by the general consumer. As the narrow perception of textiles is belied by that fact that textiles are huge part of daily life, so is automation — both sectors largely known only by the practitioners within the respective industries.

Consumers and politicians tend to pit labor and automation against one another as if their coexistence is a zero-sum-game — automation supplanting labor. Probably one of the earliest manifestations of this assumption was seen with the Luddites in England who primarily objected to the rising use of automated equipment. In the early 19th century, a 5-year-long region-wide rebellion took place during which textile workers destroyed weaving machinery and stocking frames in protest fearing that skilled textile workers would be replaced by machinery and cheaper, less-skilled labor.

There is no doubt that a fear of automation and concerns over its effect on labor have been long established, first in industrialization in general, as well as computerization and implementation of most forms of technology.

However, nothing could be further from the truth. “Each age in the Industrial Revolution has brought with it a wave of new opportunities and benefits,” said Jeff Bernstein, president, Association for Advancing Automation (A3), Ann Arbor, Mich. “From steam to electricity to computers — and now to automation —society is transformed by technological advances that increase productivity and prosperity and broaden the availability of innovative goods and services. But, more than anything, society is also transformed by new, rewarding jobs that improve workers’ health and safety and allow them to apply their innate creativity and problem-solving skills.”

Consider life before the personal computer — B.PC. — and life as we live it today after the introduction of the personal computer — A.PC. E-mail and the internet have drastically changed the opportunity for rapid communication, and information transfer happens at blistering speeds. Robotics and automation are having similar positive effects in the manufacturing environment.

“Currently we are in a phase of growth and development for automation,” Bernstein said. “As lower-level tasks are automated with advanced technologies such as robots, new job titles and industries arise across nearly every economic sector and new skills are required. The good news and the bad news is employers can’t fill jobs fast enough. Manufacturers estimate there may be as many 2 million jobs going unfilled in the manufacturing industry alone in the next decade due to a skills gap.”

Growth in robotics is real. A3 reports: “The North American robotics market had its best opening half ever to begin 2017, setting new records in all four statistical categories (order units, order revenue, shipment units, and shipment revenue). In total, 19,331 robots valued at approximately $1.031 billion were sold in North America during the first half of 2017, which is the highest level ever recorded to begin a year. These figures represent growth of 33 percent in units and 26 percent in dollars over 2016.”

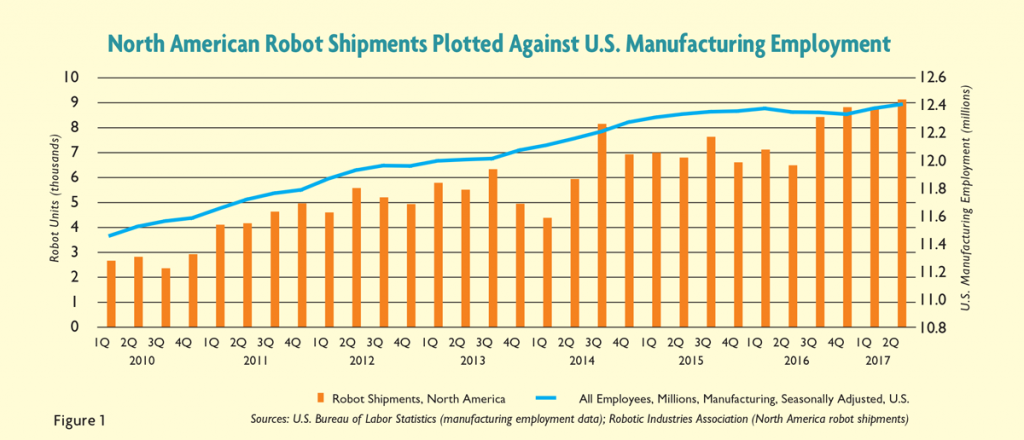

A3 also tracks the relationship between robot shipments in North America and the seasonally adjusted manufacturing jobs collected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The 2010 through 2017 Q2 quarterly chart illustrates an interesting trend. Though the intuitive result would be jobs flat or declining with robot shipments rising, that is not the case. The first quarter of 2010 had approximately 11.5 million manufacturing jobs with robot shipments to North America totaling 2,750 units. The second quarter of 2017 — the most recent data — had approximately 12.35 million manufacturing jobs with robot shipments to North America at 9,000 units. Figure 1 demonstrates the positive relationship between manufacturing employment and robot shipments.

Taking Aim At Garment Manufacturing: Enter The Sewbots

A recent Textile World Innovation Forum featured emerging robotic technology under development by Atlanta-based SoftWear Automation Inc. The technology continues to develop and according to reports, China-based Tianyuan Garments Co. has ordered 21 sewbot lines from SoftWear Automation. Tianyuan Garments has made a $20 million investment in a new facility in Little Rock, Ark. It is reported that Tianyuan produces approximately 10 million casual and sportswear garments annually for brands including Adidas, Reebok and Armani.

An article in China Daily recently stated: “From fabric cutting and sewing to finished product, it takes roughly 4 minutes,” said Tang Xinhong, chairman of Tianyuan Garments. “We will install 21 production lines. When fully operational, the system will make one T-shirt every 22 seconds. We will produce 800,000 T-shirts a day for Adidas.”

Tang said that with complete automation, the personnel cost for each T-shirt is roughly 33 cents. “Around the world, even the cheapest labor market can’t compete with us. I am really excited about this,” he said.

Just As Computers Evolved So Has The Jacquard Head

Joseph Marie Jacquard designed automated patterning equipment for weaving in 1801. The device read a series of wooden cards with holes in specific locations that instructed the loom to lift specific warp ends and release specific ends to create a pattern as the cards, which were strung together in a continuous chain, passed through the head. This concept of providing binary information/instruction for the operation of the loom and pattern control is considered one of the first automation interfaces in manufacturing and also the basis of the concept of early punch cards interfacing with a main frame computer.

Today, a strong example of this evolution comes from the research and development of Switzerland-based Staubli. Traditional heads, for many years were limited in capability. The instruction to raise or lower an end was provided to several ends in the warp and limited pattern control. With today’s mechatronic, or electro-mechanical technologies, Staubli can provide pattern control to every individual warp end, untying the designer’s hands. This technology has had implications in decorative fabric production, but also allows more complex structures to be woven, such as automotive airbags.

According to Ludovic Pitrois, North American Textile Division manager, Stäubli Corp., Duncan, S.C., it is becoming more and more difficult to find people willing to do the same repetitive jobs shift-after-shift, day-after-day. “Without robots assisting with dangerous and mundane jobs, we would lose more jobs in the United States,” Pitrois said. “Utilizing robots in these types of jobs will assist in keeping companies in the United States long term.

“Joseph Marie Jacquard’s jacquard machine was fiercely opposed by Lyon’s silk weavers, who feared the introduction of industrialization and a reduction in work force, which was over 30,000 apprentices. But by 1812, Jacquard had some 11,000 machines weaving fabrics in France alone.

“We will always see changes in technology, employee resources and automation, which is just part of continuing progress. Stäubli takes advantage of challenging itself to design even greater products and to always be ahead of the market. Today, Stäubli with its three divisions can propose full automation for any textile mill if desired.”

This article touches only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to describing automation’s impact on the textile industry. From fiber to spinning, knitting, weaving, dyeing, printing and finishing — there isn’t a textile sector that hasn’t benefitted from automation and process control. Even basic packaging and material handling have played a significant role in changing the manufacturing floor. The effect is improved quality and consistency, cost control, improved work environments and employment opportunities.

September/October 2017