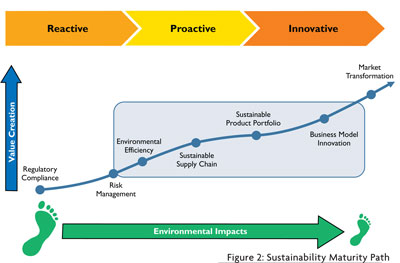

Navigating the sustainability maturity path takes a company from reactive to proactive, and possibly to innovation.

By Shelly Martin

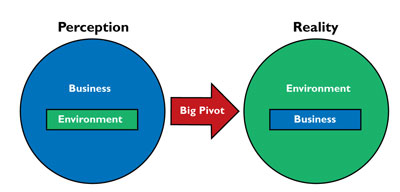

The term sustainability is so amorphous these days that companies often feel paralyzed with what actionable steps they can take to make their business and products more environmentally friendly. To further complicate the issue, there is a perception that the environment is a niche area of business operations. However, in reality all businesses must operate within the environment and its constraints.

Mega-trends like declining resources, radical transparency and increasing expectations can be thought of as analogous to other trends of the past like quality, lean manufacturing and e-commerce. These trends were nice-to-haves early on, however, they now drive business success and have become mandatory.

Value is created across stakeholders through sustainability, including product marketing via product differentiation and brand enhancement, research and development with innovation and design optimization, and finance and operations with identified areas for cost reduction. By collecting data for a life cycle assessment (LCA) study, a company learned that it was using both hot water and chlorine in a sanitizing step. Only one method is necessary to safely sanitize, and the LCA identified that costly redundancy. In addition, value can be created by identifying potential areas for risk and regulation.

Sustainability Maturity Path

The sustainability maturity path typically starts with companies being reactive and trying to comply with regulation. This may lead to risk management, where a company may use sustainability assessment to manage and reduce reputational risk and prevent the public relation crises that can result from a lack of knowledge about environmental and social impacts of product and supply chains.

From there, companies may become more proactive, which may include starting to understand opportunities to increase operational efficiency to reduce costs and environmental impacts by minimizing water, energy and materials usage. That understanding may expand to the company’s supply chain, where it may start to evaluate and monitor its supply chain to reduce environmental impacts and drive social policies.

Next, companies may move into the innovation realm where they may start to build sustainable product portfolios, as well as integrate sustainability metrics in new product development. Now, sustainability is evaluated alongside cost and performance. The company also may start to innovate when it comes to its business model, which may drive market transformation.

There are many different methodologies and tools in the sustainable product development toolbox, including environmental risk assessment, where site-specific toxicity impacts are analyzed; carbon and water footprints, which assess just one impact category; health product declarations; biomimicry; and life cycle costing.

Design For Sustainability

In addition, there are the Design for Sustainability guidelines that acknowledge the environment must be a critical consideration along with the traditional metrics around economics and performance. These general and qualitative guidelines are meant to be followed during new product development, and are based on learnings from LCAs and other sustainability tools. The guidelines are constrained by product performance requirements and consumer needs. Globally recognized, this method is intended to help companies improve profit margins, product quality, market opportunities, environmental performance and social benefits. Companies can achieve this win-win situation for shareholders, consumers, and the public by improving efficiencies in the products and services it designs, produces and delivers. This is where sustainability becomes tangible.

Materials Selection, Reduction

Selecting low-impact materials and reducing the amount of materials used is an extremely effective way to reduce a product’s environmental impacts. Eliminate unnecessary parts and assemblies, and optimize a design to reduce material usage, which in turn, reduces transportation impacts. Also increase the amount of recycled materials used in the product, and utilize materials that can be readily recycled at end of life or product disposal. Avoid energy intensive materials, such as aluminum, for products with a short life span. Companies can also find alternatives to non-ferrous metals such as copper and nickel because of the harmful emissions generated during production, and eliminate toxic materials or additives. Material selection tools and preferred materials lists can be helpful when implementing this guideline.

Optimizing Production Techniques

There are many ways to optimize production techniques including incorporating the Design for Assembly principles to reduce production steps, optimizing the design to reduce the energy used during manufacturing, eliminating or reducing surface treatments such as powder coatings, and minimizing manufacturing waste and product scrap recycling.

In addition, organizations can motivate manufacturing partners and suppliers to increase energy efficiency. Some companies have competitions at their plants to see which shift can reduce the most energy after normalizing to production. Another option is to increase the use of renewable energy. The Alchemist, a small Vermont-based brewery, moved to solar power because it made good business sense. Yes, being environmentally conscious as well as a leader in its industry was important for The Alchemist, but ultimately that was not the sole reason the brewery decided to invest in renewable energy — it also made economic sense.

Distribution System Optimization

There is a clear hierarchy when it comes to the environmental impacts of different transportation modes. Transporting by container ship and train is environmentally preferable to truck, which is preferable to air freight. Other ways to optimize the distribution system include increasing the use of reusable bulk packaging such as pallets, minimizing volumes and weight of packaging, and ensuring that all packaging is critical to function. In addition, wherever possible, products can be shipped unassembled to reduce transportation volume.

In the 1950s and 60s, Inguar Kampad, a Sweden-based furniture retailer, realized that much of the cost of making furniture was tied to the assembly process — putting legs on tables, for example — and in shipping the products. Kampad changed his business model to sell unassembled furniture that shipped cheaply in flat boxes. He undersold his competitors, who were so furious they launched a boycott against his company and stopped filling his orders. Desperate, he looked south to Poland, which had plenty of wood and cheap labor. However, few companies were outsourcing at that time, especially to a communist country. Kampad did not let that stop him pursuing his business model though, and his company, IKEA, is still prosperous and thriving today.

Reducing Impact During Use

Ways to reduce impacts during use include reducing energy consumption, making the default state the most desirable from an environmental standpoint, making sure using the product does not result in hidden and harmful emissions and wastes, minimizing consumables needed, and reducing scrap generation.

Hypertherm — a Hanover, N.H.-based company that designs and manufactures advanced cutting systems — learned that the majority of the environmental impacts of its machines, from raw material extraction through disposal, came from scrap. This led Hypertherm to start working with its customers on nesting technology. In addition to nesting, it also is exploring methods to pair clients based on the size of sheets they need to reduce waste from scrap material using the idiom that “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.”

Initial Lifetime Optimization

In an article titled “Repair is a Radical Act,” Rose Marcario, CEO, Ventura, Calif.-based Patagonia Inc., said: “We live in a culture when replacement is king … these conditions create a society of product-consumers, not owners. And there’s a difference. Owners are empowered to take responsibility for their purchases — from proper cleaning to repairing, reusing and sharing. Consumers take, make, dispose and repeat — a pattern that is driving us towards ecological bankruptcy. And as businesses, we have a responsibility to make higher quality products to help reclaim the act of ownership; make parts accessible and repair easy … . We need to enable our customers to become owners — and that will require a seismic shift in our approach. It’s a radical thought, but change can start with just a needle and thread.”

Optimizing the initial lifetime of products includes avoiding weak links that lead to a reduced lifespan and require maintenance; designing so that the product can be repaired and upgraded, as well as meet end-user needs for a long time; increasing the functionality of the product and designing the product’s appearance to increase aesthetic life.

Carpet tiles manufactured by LaGrange, Ga.-based Interface Inc. are a great example of an optimized product. The company’s traditional business model was to manufacture and distribute broadloom carpet through typical channels. This carpet lasted approximately 5 to 7 years, at which time worn out carpet was thrown out and disposed of in a landfill. Then, new broadloom carpet was manufactured and sold. Interface observed that 20 percent of the carpet gets 80 percent of the wear, and with no value at end of life, the carpet inevitably ends up in a landfill. So the company reinvented its business model and moved into the innovation realm of the Sustainability Maturity Path. Interface designed carpet tiles so only the worn out sections needed replacing. In addition, it started leasing the carpet tiles, which meant that Interface retained responsibility for the entire life cycle of the carpet tile. Interface also redesigned the carpet tile to allow for easy material separation and recycling at end of life, creating a much more sustainable carpet product.

Optimizing The End of Life System

Reduce. Reuse. Recycle. Optimizing the end of life system includes designing with recycling in mind — through material selection and designs that can be disassembled — as well as reuse of product and avoiding premature obsolescence. Other options to optimize the end of life include assessing the possibility of take-back programs and avoiding toxic elements to reduce air pollution when incinerated. Considering the Design for Disassembly principles can help ensure that a product system can be disassembled for a minimal cost and effort. These principles include making products simpler, components accessible, reducing the number of distant parts, using common parts for components like fasteners and zips, and using fewer different types of materials and adhesives. Often times these strategies also contribute to product serviceability.

The Herman Miller Mirra® Chair originally took two hours for someone to take it apart at its end of life. Two hours was too long, so Herman Miller redesigned the chair with Design for Disassembly in mind. The new design can be disassembled in 15 minutes and 96-percent of its parts now are recyclable.

Parting Thoughts

Sustainable product development is an evolving and iterative approach. It may start by brainstorming opportunities or evaluating ideas around which material is environmentally preferable, or by developing Design for Sustainability guidelines specific for your company or conducting life cycle assessments on key products. What is learned may then get integrated into product development, which may in turn lead to additional brainstorming opportunities.

Expanding viewpoints beyond a company’s four walls will open up the opportunities to reduce the environmental impacts of products. This may include considering what happens during product use and at the end of life. It’s important to strive to understand how products can be made more sustainable while increasing consumer value. It is possible for a company to move along the sustainability maturity path, from being reactive to proactive, and perhaps even venturing into the innovation realm.

Editor’s note: Shelly Martin is a project manager with EARTHSHIFT, a Huntington, Vt.-based Life Cycle Assessment software, training and consulting provider. The article is based on Martin’s presentation given at the 2015 Textile World Innovation Forum.

January/February 2016