Researchers at NC State’s College of Textiles have teamed up to develop mosquito bite resistant solutions for the consumer market.

By Dr. Andre West, Technical Editor; and Sarah Corica

At North Carolina State University (NC State) in Raleigh, N.C., there are cages filled with hundreds of buzzing, hungry mosquitoes ready to take their first ever blood meal. A researcher walks into a cage expecting the worst-case scenario. However, when emerging after 20 minutes of intense mosquito activity, amazingly the researcher has sustained only a few bites. The question is: How was the researcher protected from the hungry mosquitoes? The answer is by wearing garments made of a sleek, comfortable novel fabric. The mosquito test is part of NC State’s research to develop a highly engineered, comfortable fabric that is mosquito bite resistant to a very high level, but also free of unwanted pesticides.

The Challenge

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mosquito bites cause more deaths — 725,000 people every year — than any other organism on the planet. The majority of these deaths are caused by malaria, which is a disease caused by a one-cell animal parasite transmitted through mosquito bites. WHO estimates that between 300 million and 500 million cases of malaria occur each year and a child dies from malaria every 30 seconds.

Over the past several years, chikungunya and Zika viruses have emerged on a global scale as major human threats, causing epidemics in tropical countries with confirmed cases also reported in the United States. Current statistics provided by the Zika Foundation affirm that Latin America has experienced the highest number of Zika cases. However, the virus is spreading worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1,700 pregnant women across the United States have tested positive for Zika virus infection. In Florida alone, laboratory tests showed that 82 pregnant women were exposed to Zika virus. While the vast majority of infections occurred outside of the United States, some women were bitten and infected by mosquitoes from local populations. Zika virus likely will spread to other areas of the southern United States this mosquito season.

The Zika virus is transmitted through the bite of the mosquito Aedes aegypti; however, the virus is also sexually transmitted. If a pregnant woman is infected, the virus is transmitted to her fetus causing a severe congenital birth defect called microcephaly, which is associated with incomplete brain development. There are other health effects likely caused by Zika that scientists are working hard to identify.

The current WHO recommendation for preventing Zika transmission is to apply N, N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) or other chemical repellents multiple times throughout the day, or to wear clothing impregnated with a man-made insecticide. Exposure to such chemicals is highly undesirable to large segments of the population, especially pregnant women and children. Therefore, these individuals may be choosing to risk virus infection in order to limit exposure to chemicals. Additionally, the growing mosquito resistance to insecticides may significantly reduce the effectiveness of chemically impregnated textiles, placing the wearer unknowingly at risk.

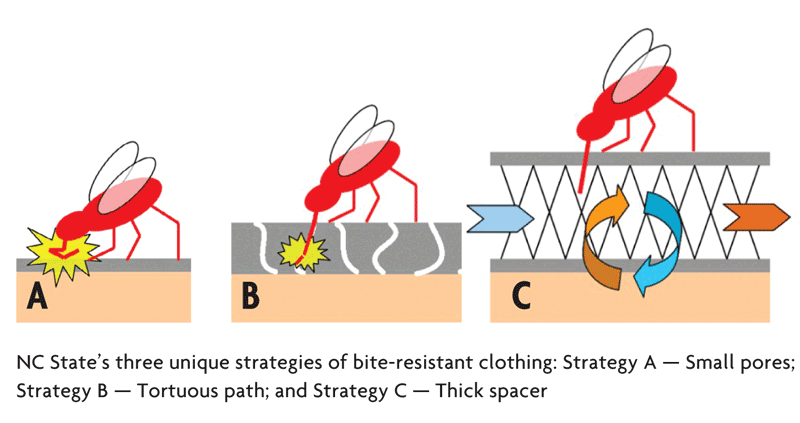

Regular clothing can provide some level of protection, but a mosquito that is looking to feed on blood can easily probe through most consumer materials including T-shirts and jeans. “It would be easy to make a fabric bite proof by just laminating the surface, but then the fabric would lose its breathability and comfort,” said Dr. Emiel DenHartog, associate director, Textile Protection and Comfort Center at NC State’s College of Textiles. Currently available non-chemical vector protective textiles offer nearly continuous or monolithic barrier layers that trap heat and moisture within the garment and can be bulky and inflexible. This type of clothing is uncomfortable in hot, humid climates where the disease carrying mosquitoes thrive. Subsequently, such protective clothing’s primary market is for hunting, fishing, other outdoor sports and military use. For the everyday consumer, this is uncomfortably impractical and lacks fashion appeal. Camouflage may be popular in the woods, but it is not appropriate for routine, everyday wear and especially not for expectant mothers. There is an urgent, unmet need for novel chemical-free garments that provide safe protection from mosquitoes while providing outstanding comfort. Non-chemical bite-resistant clothing offers a safe, sustainable and accessible solution for protection from mosquito bites.

Developing A Solution

As part of a five-year collaboration between NC State’s College of Textiles, the College of Natural Resources and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, researchers are aggressively investigating textile-based solutions to protect people living and working in locations where mosquitoes and mosquito-borne illnesses are of concern. A multidisciplinary team consisting of entomologists, textile engineers, textile designers, comfort analysts and protection specialists is uniquely positioned for this challenge. The team has been collaborating on the development of a new generation of non-chemical vector protection, and has cultivated relationships with military and industry partners who are rapidly scaling up their technologies to move these critically needed garments to market.

Dr. Marian McCord, associate dean for Research in the College of Natural Resources, is leading the effort to develop these innovative protective fabrics and clothing. “Our research has brought together a unique group to study how mosquitoes interact with textile structures and humans,” said McCord. “We use our combined knowledge to design, model and prototype chemical-free fabrics that provide exceptional comfort and protection from mosquito bites.”

As part of the collaboration, Dr. Michael Roe and Dr. Charles Apperson raise and maintain colonies of mosquitoes and conduct four tiers of textile testing covering the range from small fabric swatches to whole garments tested in walk-in cages and under real-world field conditions. Along with their postgraduate students and technicians, they have developed a new laboratory assay system that facilitates rapid screening of prototype textiles and garments.

The fabrics are designed, developed and tested through collaboration with international fabric manufacturers and the textile and entomology labs at NC State. The goal is to find the delicate balance between offering a breathable, comfortable fabric at the same time as providing a defense against mosquitoes. Using CAD software and measurements of the mosquito’s needle-like mouthparts, known as the proboscis, the fabrics first are virtually modeled to prevent the mosquito’s proboscis from penetrating through the fabric to the skin. Fabric prototypes are constructed and then tested for bite resistance. The testing was designed determine the mosquito’s ability to penetrate the fabric after landing on its surface. Fabric color and the wearer’s body odor guide the mosquito to a potential victim. Mosquitoes are typically attracted to dark-colored fabrics. An open and breathable fabric allows more odor to permeate the fabric; however, after landing, mosquitoes get frustrated if they are unable to pierce the fabric. Repeated landings and probings indicate that mosquitoes are trying to find an area of the fabric that is vulnerable to penetration. The researchers used objective video analysis to study the interaction of mosquitoes with the textile surface. An examination of the mosquitoes for evidence of successful blood feeding coupled with the number of landings allows the research team to comparatively evaluate each fabric prototype. Fabrics found to have a high level of bite-resistance are then evaluated for comfort, including air and heat permeability, and moisture wicking. This information along with the bite-resistance data has allowed Dr. Kun Luan, a post-doctoral researcher assigned to the project, to develop a model that predicts the bite-resistance and comfort of varying fabric designs. The goal is to develop a multitude of fabrics including undergarments and outer garments that will suit a multitude of conditions.

The research has led to the development of a design system that can be used to produce a variety of fabrics that provide protection from insect bites for a wide consumer market. The design system can utilize a variety of fabric structures, including woven, knitted, and nonwoven materials, and may incorporate other non-textile materials or substances. Evaluation of fabric comfort is performed based on its end function. “These fabrics are designed to prevent the mosquito from penetrating all the way to the skin, but are porous enough to allow air permeability and moisture management,” DenHartog said. Garments are then made from these fabrics and constructed in such a way as to allow unhampered movement and a high range of motion. Areas of the body that may be more attractive to a mosquito — for example the ankles and behind the knees — as well as areas over which the fabric may deform — including elbows, knees, and a pregnant woman’s abdomen — can be provided additional protection based on the garment’s construction. Additional protection can be achieved with a double layer of fabric or by further increasing the density of the material in those areas of the garment.

Apperson said: “Women, especially expectant mothers, are looking for reliable and safe products that can protect them and their babies before, during and after pregnancy against the Zika virus, as well as other viruses transmitted by mosquitoes.”

“Now that we know the Zika virus causes severe birth defects and is associated with other adverse health effects, there is even greater need to protect people,” McCord said. “This is not just an issue for pregnant women. We need to protect women’s partners who can sexually transmit the virus as well. It’s also a security issue for our military troops being sent into disease endemic countries, and it is a workforce issue for employees who are outside in these areas. Economical, accessible and sustainable vector protective clothing that does not use chemical repellents may be much more appealing to many and would limit the need for application of repellents to exposed skin.”

As the testing and design continues, researchers have been developing bite-resistant fabrics and garments for commercial use within the parameters associated with specific target end users. “Because of the strength of our diverse team, we have been able to build a product line with innovative attributes and functionality that is ready for commercialization in a market that we believe is in dire need of a solution for preventing mosquito-transmitted diseases, such as Zika,” McCord said. According to Roe, the textile and garment products have been stringently tested in NC State’s entomology labs and proven better than 98-percent effective under extreme worst-case scenario mosquito exposure.

Commercializing The Technology

To take this ground-breaking research from the lab to market, the team has worked closely with the Office of Technology Commercialization and New Ventures (OTCNV) at NC State to identify opportunities and file patent applications. The OTCNV is continuing discussions with industry partners to maximize the commercial potential of the technology and to provide new options for protection against the Zika virus for millions of individuals in high-risk areas.

Presently NC State has a limited licensed commercial partner in Har-Son Inc., Midwest City, Okla. Its RynoSkin™ brand has a national reputation for providing bite-resistant clothing for the hunting, fishing, military, and police clothing markets. The company’s previous product could not protect against mosquito bites, but guided by mosquito and comfort testing at NC State, Har-Son has produced an undergarment that is 98-percent bite-resistant in walk-in cage tests. The product now is sold to national retailers under the name RynoSkin Total.

Vector Textiles

The NC State research team believes there are many markets available for mosquito protection garments, but feel maternity is the highest priority market. Currently, no companies are focusing solely on the production and marketing of mosquito bite resistant clothing for protecting expectant mothers from Zika virus without the use of chemical repellents. Consequently, the researchers have formed a company called Vector Textiles Inc., Raleigh, N.C. Vector Textiles will engage in research, product design and development, and real world testing of a multitude of fabrics that act as barriers for protection of people, animals and even plants from insect infestation. “At this point, with Zika virus of predominant public concern, we feel compelled to develop a maternity brand,” said Dr. Andre West. “Furthermore, we will have our product on the market shortly under the brand name Pro-Tex Maternity. We are using the crowd funding source Indigogo not only to raise funds to purchase materials and provide cash flow for manufacturing, but as a way to inform and notify the general public that there are alternative, safe and sustainable methods available for their personal protection from mosquitoes.”

The first maternity clothing line will be targeted at consumers in Latin America and the southern United States. The target consumers are women between the ages of 15 to 49 years of age, which represent approximately 170 million potential consumers. “Our products contain no insecticides and are comfortable for indoor and outdoor wear in hot, humid climates,” West said. “The first garments will come in two levels of protection, the first being innerwear that can be worn as an undergarment or a base-layer and will include leggings — some under the belly, some over the belly — perfect for comfort while pregnant, as well as fitted tops of different lengths. These can be worn underneath regular clothing to provide a high level of protection at the same time as allowing the consumer to wear their regular clothes, be protected and still feel comfortable.”

The second garment group will be a specifically designed outerwear maternity line that will offer effective protection against biting insects. In the future, Vector Textiles wants to integrate digital printing technologies to enhance the line with protective yet fashionable apparel products to meet consumers’ demands. The design of the products also will consider population diversity and consumer aesthetic demands following the latest fashion trends. Subsequent future design efforts will be oriented to daily wear and casual business apparel products.

Bite-resistant garments will be affordable in the U.S. market. According to West, predicted retail prices will be in line with currently available specialized maternity wear. Vector Textiles is exploring the Toms concept of improving lives and would also like part of the proceeds from retail sales to subsidize a basic product line of protective apparel for low-income women in the countries hardest hit by the Zika virus. “We hope in the near future that humanitarian organizations will be able to purchase in bulk for distribution to displaced populations at risk of mosquito-borne illnesses,” Roe said. “Doctors and midwives will be able to sell products through their clinics; governments could subsidize the clothing for lower-income women at risk. We are also working on reusable garments deployed for health workers.”

“We will continue to improve on the fabric and garment construction as well as the style of garments to make products not only for a greater good but for a multitude of different end uses,” McCord said. “Certain segments of the world population are more at risk right now, so that is where the focus is.”

Editor’s Note: Sarah Corica is the director of marketing and communications for NC State’s College of Natural Resources.

For more information about the research, contact Dr. Andre West at 919-515-6650; ajwest2@ncsu.edu.

May/June 2017