Part one in a two-part feature on textile education focuses on college and university offerings.

By Jim Kaufmann, Contributing Editor

S

ome 20 years ago, Textile World published an article about textile education offerings in the United States (See “Making the Grade,” TW, January 2002). Ironically, or maybe not, many of the industry specific comments contained in the article remain entirely viable if not prophetic in 2022. Some of the comments included:

- “Over the last 20-plus years, the U.S. textile industry has shifted and been altered dramatically, yet the need for qualified, well-educated individuals to assume leadership roles remains constant.”

- “With the growing prevalence of niche markets and specialized products in the U.S. textile industry, colleges and universities are offering more diverse programs in order to meet the needs of the industry and provide more opportunity for graduates.”

- “A lingering question in the minds of many prospective students concerns the wisdom of entering an industry many consider to be declining?” The response? “There will always be a textile industry in the United States! No doubt it has changed over the years and will evolve even more in the years to come. Textile management, marketing, chemistry and engineering skills are vital today. I would heartily encourage anyone considering a textile education to pursue it. There is still a lot of opportunity out there!”

Words quoted more than 20 years ago, but each still resoundingly rings true in today’s textile arena.

According to David Hinks, dean of the Wilson College of Textiles at North Carolina State University (NC State), Raleigh, N.C.: “Significant changes in the textile industry in the 1980s and ‘90s with a collective move to producing textiles offshore resulted in closing down many textile mills in the U.S. and intensified the shift towards a negative opinion of the textile industry as a whole. This had a direct effect on the elimination of schools of textiles at colleges and universities and a change in programs specific to textiles being merged into materials sciences programs. As other universities moved away from textiles, it created a challenge, but it also created opportunities for NC State. We did the opposite and doubled down on maintaining the textiles name in our Wilson College of Textiles, textile programs and in our focus on the textile industry.”

Today, NC State’s Wilson College of Textiles remains the largest school focused on textiles in the United States and offers the most comprehensive program offerings devoted to textiles and the textile industry. According to Dean Hinks, “Before the shift, there was a healthy collaboration between traditional textile schools like Clemson, Georgia Tech, Philadelphia Textile, NC State and others. This had become a little eco-system that raised everyone up through a healthy competition for students and also occasional joint programs.”

Today, some of the other textiles schools mentioned by Dean Hinks are still offering textile programs in one form or another, but like the industry it supports, there have been many changes.

“While textile manufacturing at large was exported out of the U.S., you have to understand that the design, engineering and development functions never left. These functions are still thriving in the U.S. and manufacturing is returning,” noted Mike Leonard, academic dean, School of Design and Engineering in the Kanbar College of Design, Engineering and Commerce at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. Philadelphia University, formerly known as Philadelphia Textile, merged with Jefferson University in 2017, however, textiles continue to be an integral part of its academic offerings. “Yes, textile classes are smaller than decades ago, but they still provide excellent training grounds for addressing today’s textile endeavors that continue to be more complex, involved and engaging,” Dean Leonard said.

Second Verse, Same As The First

While not much has changed, seemingly everything has changed in today’s textile industry. As of this writing, the industry is dealing with the ongoing global pandemic, labor shortages, supply chain concerns, off shoring and reshoring, sustainability efforts, Industry 4.0 adoption, technological advancements, and a broadly expanding list of unique applications. This is not to mention the never-ending battle to reverse the textile industry’s perpetually dismal and negative image.

“In reality, the textile industry continues to be alive and well, and all that textiles do for us remains incredibly important and ever expanding,” said Dean Leonard. “Upon becoming Dean, I made everyone promise to ‘stop talking about textiles in the past tense!’ We need to be positive and looking forward. The main thing we can do for textiles, including for our current and prospective students, is be able to describe a future, a real future for the textile industry, not just give up and say it doesn’t exist anymore.”

Dean Hinks offered a similar view: “The prevailing images that the textile industry has left and all that remains are rusted out buildings and hazardous sites or that its merely not exciting or ‘techy’ enough to garner the interest of younger generations is just simply not true. I always enjoy seeing people’s faces when they come to our facilities for a tour and see all that we’re involved in and where our students end up in industry. They had a vision in their mind that predictably isn’t our reality.”

Many in the industry agree that the timing is right for the industry to mount a collective effort to effectively rebrand textiles, which if presented accurately, would only help in attracting new blood to textiles.

“We find many young people seem to have a bad taste for textiles due to the old-world exposure and faded beliefs originating from adults in their lives,” said Jasmine Cox, director of Textile Technology Programs and Business Innovation at Gaston College’s Textile Technology Center, Belmont, N.C. “There really needs to be more exposure through a positive industry-led effort to reach out to students and young people in general in order to erase these old perceptions and reintroduce today’s textile industry.”

“We need a collective effort throughout the industry to come together to show today’s amazing world of textiles,” Hinks said. “It’s incumbent on us to educate our society on the whole world of textiles, not just the clothing portion, and how textiles as a whole continue to improve the quality of our lives and livelihood.”

New Blood

Individual and collective programs are being developed and put into motion that, to a baseball fan, sound very similar to creating a “farm system” for identifying and growing the textile industry’s talent pool. The Textile Technology Center at Gaston College recently introduced its Textile Academy (See “Breaking New Grounds,” TW November/December 2021) offering a variety of education options in order to “cultivate highly skilled workers of all levels for local textile industry employers.”

“The Textile Academy is a culmination of our efforts to meet the local textile industry’s needs and fill a perceived void based on the feedback received from different textile industry avenues,” Cox offered. “A textile education today really depends on the individual’s interests and goals. Most universities only offer four-year or higher degreed programs that may not be right for many individuals. It’s great to have university graduates go into staff positions, but you still need training for workers, technicians, shift managers, and others who may only really need a couple of days to get familiar with textiles. Or perhaps an option for someone just looking to learn more about textiles to get started, who might then entertain a more in-depth program, possibly leading to a four-year program.”

The Textile Academy is a function of the continuing education department at Gaston College. It has established several program offerings akin to attending a trade school, and accredited textiles specific courses that can lead to a two-year associates degree. Gaston College and the Catawba Valley Community College (CVCC) recently announced a “bilateral 2+2 articulation agreement” with NC State’s Wilson College of Textiles. This agreement provides the opportunity for students who graduate from the Textile Technology Degree program with a two-year associates textiles degree — initially in Textile Technology or Textile Management tracks — and who meet eligibility requirements, to possibly transfer those credits into a Bachelor of Science in Textile Technology degree program at NC State. “We’re finding that not everyone is ready for a four-year college commitment, so we are developing these programs as a way to provide an easier entry into academics through local colleges in the form of training classes, certificate courses and associates degrees,” Dean Hinks noted. “Community colleges generally have a high percentage of first-generation attendees and we need to gain and provide access to these individuals. Our intention is to start these partnerships with Gaston and CVCC and learn as we further develop the program. Then there’s no reason not to take a similar approach with other community colleges, continue to grow the program offerings, and subsequently the talent supply. The industry’s talent pool needs to become more diverse in terms of heritage, income levels, and ethnicity, and this program will indeed help.”

This collective effort is geared towards supporting the rural North Carolina textile industry base where according to Dean Hinks, a recent study indicated that within a three-hour drive of Raleigh, one can encounter approximately 50 percent of the U.S. textiles industry. “We really need to put ourselves in a position to supply talent to fill the needs of the textile industry at all levels. Through this program, we can incorporate community college efforts to supply ground level needs as well as potentially feeding those interested into NC State.”

Soft Goods Versus Hard Goods Mentality

Paul Latten, director of Research and Development at Southeast Nonwovens and a graduate of NC State with a Bachelor of Science degree in Textile Engineering and Science, said: “My textile degree has proven to be useful, valuable and made it easier to relate to both soft and hard goods throughout my career. Soft goods offer a unique value proposition that you need to understand from the onset. For example, how does a polymer and/or fiber behave individually and also in a fabric structure. Then, how does each influence the intended application. This adds a complexity that isn’t necessarily apparent when dealing with hard goods. In fact, one could argue that it’s easier for someone educated in soft goods to transition into hard goods than vice versa. Soft goods just necessitate a different way of thinking.”

Another consideration, often overlooked, is that a textile education tends to be a more effective way to grasp and understand the many layers intrinsic to textile technologies, related terms and nuances specific to the soft goods industry. There is a unique, if subtle, difference in philosophies associated with soft goods compared to that of hard goods such as steel, wood or concrete. According to Dr. Brian George, director of Engineering Programs at Thomas Jefferson University: “We’ve noticed that traditional mechanical engineers transitioning into textiles do tend to have troubles initially. They’re generally amazed by how many variabilities must be considered that factor into textile product decisions. There can be so many different options or paths available to make a textile perform a specific way, which differs greatly from common hard goods perspectives. It’s just a different way of thinking.”

To be clear, having a textile education is not a mandatory requirement for someone to work in the textile industry. All are certainly welcomed and there are countless examples of men and women working throughout the textile industry who did not have a prior formal textile education when hired. Many textile companies historically have simply taken it upon themselves to teach their new hires what it believes they need to know about textiles to do their jobs. However, a textile education does make the indoctrination and assimilation period for new hires shorter and more efficient. The 2002 TW education article noted that, “The general estimate is that it takes roughly two years to bring a generic major up to the same use level as an entering textile major at a support cost to the hiring company of approximately $200,000 per year.”

In And Out Of Sorts

As the textile industry has shifted and evolved over the past few decades — from an industry focused on traditional textiles to one manufacturing high-performance products using increasingly intelligent machinery — so too has the approach taken by institutions of higher learning in redefining the make-up and options available for education. As mentioned by Dean Hinks, NC State has continued to maintain its focus on textiles while other traditional textile schools have incorporated their textile offerings into materials-, science- or fashion-specific curriculums. However, textiles can still be prevalent in these programs depending on the student’s course of study. “In the 90s and 2000s, we were finding that students and colleagues who had a textile engineering degree were having trouble breaking out of textiles and transitioning to, or being accepted in, other industries because of the potentially negative connotations associated with textiles, especially as engineering tools,” Dr. George said. “We heard things like ‘what do they learn about socks or towels that is relevant to our industry?’ So, we reasoned that a more general engineering degree with a concentration in textiles, for example, would allow them to break out into other industries without the textile stigma.”

Along with Jefferson, Auburn University, Clemson University and the Georgia Institute of Technology have transitioned their textile programs into their College of Engineering. For example, Jefferson currently offers a B.S. degree in Engineering with a concentration in Textile Sciences and a B.S. in Textile Product Sciences. Jefferson also offers a Master’s in Textile Technology or a Master’s of Science in Engineering with a textile engineering concentration. And for anyone interested in continuing, Jefferson also offers a doctorate in Textile Engineering and Sciences. Texas Tech University’s textile programs are now part of the Department of Human Sciences.

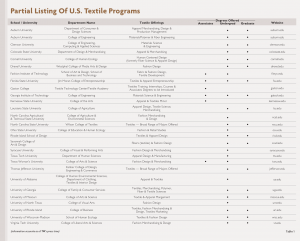

There are, however, a growing number of colleges and universities that offer a variety of textile- and/or fashion-related programs (see Table 1), and interest in textiles is continuing to grow. “There does seem to be a change in perspectives about textiles as people start learning and seeing more about how textiles can be used,” said Dr. George. “Interest in textiles as an engineering and design medium is certainly growing and we’re finding that there are more jobs than applicants. People with textiles knowledge can essentially pick and choose where they want to go and what industry they want to be a part of. That wasn’t the case 20 years ago.”

Emphasis On Technology

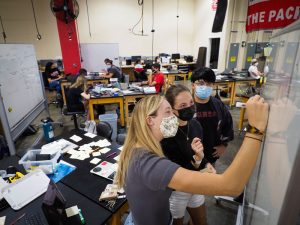

“Textiles are definitely complex; and delightfully so,” advised Dean Leonard. “Because of this inherent complexity, we have altered our course offerings to be more inclusive in nature. We want our designers better versed in the technical details of textiles; and conversely, we want our technology and engineering students to be more aware of the design aspects of textiles to better understand the edges of each discipline.” A bigger emphasis on technology across the board helps instill this sentiment at most all universities. Design technologies and patterning software continue to become more complex for both knitting and weaving machines as the designs and applications also become more complicated in fashioning, and 3D knitting and jacquard weaving.

Priya Jyotishi, a graduate of Drexel University with a Masters in Science, Fashion Design and Research, who now works as a textile technologist for Propel LLC, Pawtucket, R.I., actually sought out the technical component when evaluating her school and program options. “The design execution is becoming more technical in nature,” Jyotishi said. “So, having that exposure from my classwork and labs has been very helpful in my current work.”

This technical growth is complicated by the fact that there isn’t a consistency to the design programs or interfaces used by different machine manufacturers. Programs can literally change from year-to-year and even model-to-model. A ground level exposure in school to machine design program fundamentals has proven to be very helpful to designers and engineers alike.

Collaboration Is Key

Collaboration is also a common term used at the universities. “We teach collaboratively at Jefferson,” Dean Leonard said (See “A Study In Collaboration,” TW, September/October 2020). “Departments collaborate with other departments. Students collaborate with each other and with our professors. And in all aspects, we engage our alumni and continue to build our collaboration efforts with the textile industry. Our goal is to create a hybrid student through collaboration. This allows them to address problem solving effectively from all sides and make them more grounded in what they do. You really can’t design or engineer things from only one perspective each time.”

At Gaston College’s Textile Academy, a similar theme rings true. “We’re hoping to rebuild the bridge between industry, both locally and nationally, and education through our collaboration efforts,” Cox said. “The textile industry in the U.S. continues to grow and change and we need to be able to support it throughout all levels.”

As the textile industry becomes more global in scope and nature, many of the universities also are extending their collaboration efforts globally by offering, projects with colleges and universities outside of the United States, international internships, and study abroad options. In most cases, these opportunities are geared specifically to the student’s interests.

Not to be outdone, NC State — with close to 1,000 students enrolled in undergraduate- and graduate-related programs as of Fall 2021, and countless numbers of alumni — is focusing its collaboration efforts on an even grander scale. “Taking a much broader world view helps our students to become more confident, more worldly and better prepared for what awaits them after their graduation,” Dean Hinks said. “We want to support the entire student, not just a part of them.” As a result, at NC State there has been an increase in study abroad options along with a heightened awareness of intern programs offered through local and international textile companies. To carry these efforts even further, the Wilson College of Textiles is preparing to launch “Wilson for Life,” a new directive intended to foster a lifelong relationship with the school. “We want earning that degree to be a mile marker and the beginning of a lifelong relationship that supports our graduates throughout the twists and turns of their career journey,” Dean Hinks said. “This program will include lifelong career support, increased community engagement and relationship building opportunities, and augment what has been done in the past only in a more formal manner. The cost of a four-year degree keeps increasing, and we need to demonstrate the real value of that degree is not just those four years, but much more.”

The Value Of A Textile Education

Textiles continues to offer a more unique value proposition, which really matters in today’s world. Today’s textile industry for a new hires can include most anything from polymer composition and additive chemistry to manufacturing, fashion, industrial and technical fabrics, or fiber reinforced composites. Given this and the fact that student placement rates are almost 100 percent, it’s fair to say a textile education can be an e-ticket ride to a rather interesting career and a wealth of opportunities!

Editor’s Note: Part two of this feature, to be published in an upcoming issue of Textile World, will look at continuing education and training courses offered by the industry’s various associations.

January/February 2022