Bear Fiber Inc., a forerunner in the textile hemp fiber movement, sees tremendous opportunity for hemp in the U.S. textile, apparel and fashion arena.

By Rachael S. Davis, Executive Editor

Buzzwords come and go in the textile industry, but two words in particular have had some staying power over the past handful years — sustainability and hemp. Not surprisingly, the two words are connected, and one man chasing hemp as the next big thing in sustainable fibers is Guy Carpenter. He is not alone in the United States in that endeavor but is widely acknowledged as one of the forerunners.

Carpenter’s experience in the fiber industry goes back many decades, and his exposure and interest in hemp began when he was working in Europe. He eventually co-founded Bear Fiber Inc. in 2017 when he realized no one else was exploring the potential of hemp fiber in the United States.

Bear wants to be the supplier of choice when it comes to high-quality textile grade hemp fiber, and the company is highly invested in reestablishing American hemp as a source of sustainable, natural fibers. The company operates under the trademarked motto “Hemp Makes It Better™,” and it’s a motto Carpenter firmly believes in.

Hemp! Why Hemp?

While a hot topic and buzzword in the textile industry lexicon, hemp for textile use is not new. Hemp is acknowledged as one of the earliest known textile fibers and has come and gone from the textile landscape throughout history. However, hemp has a checkered history in the United States due in part to its association with cannabis and the negative thoughts this connection invokes.

The current rebirth of the fiber in the United States coincides with the 2018 Farm Bill Act that removed industrial hemp from inclusion in the Controlled Substances Act (See “Hemp: A Reintroduction To One Of The Original Textile Inputs,” Textile World, November/December 2020). The bill made commercial production of hemp legal in the United States, and thus, an opportunity was born for textile hemp fiber.

Current market research reports looking at the value and potential growth of the hemp fiber industry vary depending on the market research company. But two things researchers agree on is the growth numbers are in the billions of dollars and increased use of hemp in the textile industry is driving the growth.

Carpenter isn’t focused purely on dollar signs. He understands the significance and widespread value of the industry from the farmer to the textile producer and wants to help develop the United States hemp fiber industry while also continuing to grow the global hemp industry. “We’re trying to create an industry, not just run a business,” he emphasized. “They say there’s 25,000 different things you can do with hemp, but my brain is tracked to one thing and one thing only — textile grade fiber for apparel and footwear.”

What Hemp Brings To The Textile Table

The benefits of hemp fiber, a member of the bast fiber family, are not in dispute. Hemp is an environmentally friendly and sustainable fiber. It is strong, durable and absorbent. It also has natural antimicrobial properties and exhibits resistance to ultraviolet light. Its benefits in textile apparel applications are evident.

“Using at least 30 percent hemp in a yarn blend with cotton makes for a new natural fiber-based technical textile, which is strong and will last longer,” Carpenter noted. “The blend allows for the familiar touch and comfort feel of cotton made better by the positive attributes of hemp.

“I should talk about sustainability, regenerative agriculture, carbon sequestration, and hemp’s strength and technical attributes,” Carpenter said. “But I like making apparel with hemp because it feels good, and it lasts a long time. It’s that favorite jacket, sweatshirt, T-shirt, socks, shirt or jeans that just keeps getting softer and softer over time. Hemp wears in, it doesn’t wear out!”

Growing Hemp

China and Europe already have established industrial hemp markets growing the plant for food, cannabidadiol (CBD) and textile use. There are many, many different hemp varieties depending on the end use for the plant.

Hemp grown for CBD, marijuana or food uses is cultivated to be as leafy as possible. More branches mean more buds and flowers where the cannabinoids are concentrated, and the plants are grown with ample space between each plant to allow this leafy growth, which also encourages thicker, stronger stalks.

Hemp plants are similar to trees with branches and everywhere there is a branch on the stalk, there is a knot hole. “Each knot hole is an interruption in the fiber growth of the long, straight fiber that we require for textile applications,” Carpenter said.

“Where fiber fineness is not a consideration, grain hemp stalk can be used,” Carpenter said. Applications may include nonwovens and composites for construction and geotextile products. “Because the stalk has matured by necessity to support the weight of the flower and then the grain itself, the fibers become stiffer and thicker in order to support the weight at the top of the stalk. These fibers are inherently too mature for textile yarn spinning applications.”

Therefore, the approach for growing hemp for high-quality textile fiber is quite different. The seeds are planted very, very close together, which encourages the plant to grow tall and thin with little in the way of branches. Hemp grows rapidly — the stalk can be 10 inches tall in as little as 14 days — and as the plant develops its first set of leaves, the leaves create a canopy that inhibits sunlight from reaching the ground, thus providing natural weed prevention so little to no herbicides are required.

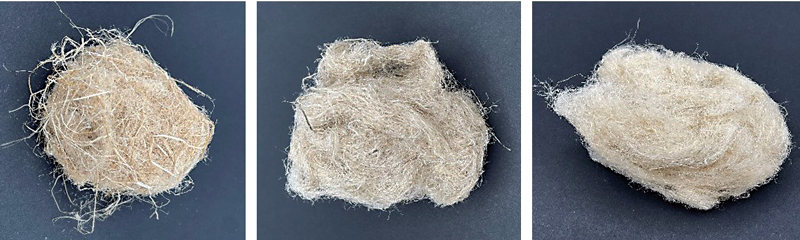

Once the plant is ready to flower, and before the fibers get too tough for textile applications, the fields are cut and the stalks lay on the ground to begin dew retting. This is a natural process whereby bacteria begin to degrade the pectin, which is the gummy substance that binds the fiber to the woody hurd — or center — of the stalk (See Figure 1). After retting, the stalks are baled and sent to a processor to be decorticated — a process that physically separates the fiber from the hurd in a manner similar to any bast fiber process. After decortication and refining, the fiber is ready to be degummed to remove the lignin “glueing” the individual fibers in bundles and ribbons. Extracting the lignin allows the fiber bundles to release the individual fibers during the next process — opening.

Developing The U.S. Hemp Industry: The Journey

Hemp is a natural fiber and as such, producing the best fiber for apparel and fashion uses is not an exact science. Carpenter has spent extensive time in China over the past 25 years learning about hemp farming and hemp fiber production, but knows he still has a lot to learn.

“It’s been a learning process here in the United States using the equipment available,” Carpenter said. “It’s been an adaptive process, and we have not always been successful!”

Cotton has enjoyed the benefit of decades of research and development in the United States, which along with the work the farmers do, means the United States grows the best and most consistent cotton the world.

To spin yarns, fiber consistency is imperative. Providing that consistency to the hemp industry is Bear Fiber’s biggest challenge.

To start, farmers need to grow the hemp variety that is best for textile fiber use as well as the best variety for the region in which they are based.

Encouraging U.S. hemp farming briefly led Bear Fiber into the hemp seed business. “Everyone wanted to grow European hemp varieties for us, and these varieties were not developed for textile grade fiber, or developed to grow successfully in the United States,” Carpenter said. “We were getting maybe 8 percent useable fiber from the stalks, whereas the Chinese had specifically been developing varieties for greater amounts of textile grade fiber that could be grown in a faster manner.” So, Bear Fiber began importing Chinese seeds, which was a whole new educational process that required forming a new business network.

Hemp is a hardy plant that can be grown in a variety of climates, although it prefers a temperate climate and fertile, loamy soil. “Honestly, we don’t yet know where the best place to grow hemp in the United States is,” Carpenter confessed. “But we are pretty sure where hemp can grow in 100 days or less and likely provide double digit textile grade raw fiber yield, which is what we are looking for. This also allows us to pay a fair price to the farmer or processor for the fiber.”

Carpenter believes there is a real opportunity for farmers, especially those in agriculture and textile producing states — such as Georgia, and North and South Carolina — where the spinning mills already exist. “However, we intend to be agnostic,” Carpenter said. “If the fiber is healthy and clean, we’ll ship it from any state in the union. It’s worth it.”

Bear Fiber currently is using textile hemp from North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Montana — where there are quantity processors that have fiber available to date. But the company also is working with newer processing operations in Missouri, Alabama, Texas, California and Oregon. “We want to help grow this industry and help create opportunity for the farmers across the country,” Carpenter said.

“Some states — including New York with a $10 million investment — have programs in place to advise and financially assist American farmers who risk growing this new fiber crop,” Carpenter continued. “But farmers have to pay bills just like anyone else, and if they can’t get real support, they can’t take the chance.”

North Carolina has a fantastic advocate at NC State University by the name of Dr. David Suchoff, who is an alternative crops extension specialist in the department of Crop & Soil Sciences in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Dr. Suchoff heads agricultural research stations and leads a national public/private hemp consortium. The goal of the consortium is to address many of the issues relating to the hemp industry through collaborative research with other institutions across the country. Suchoff also plans to expand hemp farm fiber outreach opportunities with emphasis on underserved farming communities.

Dew retting harnesses moisture that develops overnight to encourage bacteria growth. “That makes it harder to get good textile fiber from hemp grown in Montana where there is no dew,” Carpenter said. “But there are different varieties of hemp, and we are learning about techniques to promote bacterial growth for retting in geographic areas that don’t enjoy the same climate as say North or South Carolina.”

Decortication also is key step in hemp fiber processing to preserve the textile grade fiber. Any kinks or damage caused during decortication may weaken the fiber, which results in poor performance in downstream processing. “Great care has to be taken when decorticating textile grade fiber,” Carpenter said.

Bear Fiber’s Expertise

Circling back, one of Bear Fiber’s goals is to be the supplier of choice when it comes to high-quality textile grade hemp fiber. “Where Bear Fiber comes into play is we know how to separate the hurd and clean the fiber to where it needs to be so it can then be put through the wet processing of degumming,” Carpenter said. “The most important thing about this process is that raw fiber with any percentage of hurd must be cleaned and refined. Fiber with any percentage of hurd mixed in is not as valuable as raw fiber that is cleaner.”

Carpenter said in American hemp fiber processing currently, the raw fiber is anywhere from 1 to 6 inches long in bands or ribbons gummed together. Bear Fiber uses an alkaline process to degum the fiber. There are many methods available to degum hemp fiber — including boiling, electrification, acid and enzyme techniques — but Carpenter likes an alkaline process developed by the Chinese because it’s simple and cost effective. The end goal is fibers that are 1 to 2 inches long.

“We’re trying to achieve a uniformity in the degummed fiber so that it can be blended with other fiber from the United States,” Carpenter said. “Each bale is tested before degumming against a standard formulation, but we might have to adjust the alkalinity or the chemistry in some way if we need to lighten the fiber to achieve a more consistent fiber grade based on where the hemp came from and how well it was retted.”

Hemp fiber is valuable. Carpenter shared that currently, hemp fiber compares to alpaca fiber in price. “Right now, it’s still pretty expensive because everything that has come through our pipeline so far has been part of the development process,” Carpenter shared.

Carpenter has been busier than usual over the past several months. The company relocated within North Carolina from Wilmington to Morganton, to be closer to manufacturing partners. “We hope one day to grow into our own spinning and will focus on spinning natural fibers, recycled fibers and regenerative fibers” Carpenter said. “In Morganton, I’m surrounded by 120,000 pounds of recycled fiber. Material Return [a solution for custom circularity that works with manufacturers and brands to transform textile waste into new products], for example, is here in Morganton and it has a Smart Wool return program for socks. Bear Fiber looks forward to eventually blending innovative technical yarns comprised solely of natural, sustainable, recycled and regenerative fibers.

“The hemp fiber industry doesn’t really have a competitive environment yet,” Carpenter mentioned. “We haven’t produced enough fiber to make a difference in any market. To date, the only commercial products made using U.S. hemp and manufactured in the United States are Bear Fiber socks.” The socks are developed and knit in partnership with the Manufacturing Solutions Center in Conover, N.C.

“Our industry manufacturing partners have been receptive to hemp and a number of companies have been true first movers,” Carpenter shared.

Collaborative Approach, Partnerships Are Key

Carpenter has embraced a collaborative approach to growing the U.S. hemp industry. He has worked with brands, both big and small, and consults with and mentors anyone wanting to learn more about hemp and the opportunities it presents. “We all work together better than alone,” he said. “I always prefer to look for partners and establish relationships. We are all allies working together to create a market. I’m willing to help and share the knowledge I have in order to advance and grow this industry.”

While Carpenter is widely acknowledged to be a hemp “guru” of sorts, he does want to make it patently clear that he is not any sort of isolated Don Quixote character operating independently. “There is no way that one person could have achieved much without the help of dozens and dozens of people who believe that hemp fiber is an important and viable asset to the American textile and apparel industry,” Carpenter stressed. “It’s been a journey and I wouldn’t be where I am without the help I had along the way.

“I’d like to name and thank everyone, but there’s just not enough space in the magazine. For Bear Fiber, farmers, processors, spinners, weavers, knitters, finishers, the Textile Technology Center, NC State’s Wilson College of Textiles, VF Corp. and Vans all have been working to create a circular collaborative effort. We also would have been at a dead stop for months without processing help and fiber from IND Hemp — an amazing team that works with farmers to grow hemp out West and processes fiber, grain and hurd in Montana.”

“Guy Carpenter was the first person I turned to when I wanted to learn about Made-in-USA hemp, and he has continued to be a source of both technical and business knowledge as the Wilson College of Textiles and NC State University develop our position in growing, cultivating and manufacturing hemp,” said Dr. Andre West, director of the Zeis Textiles Extension for Economic Development at NC State’s Wilson College of Textiles. “Guy’s passion for a sustainable future led him to embrace hemp early on as a solution and build a unique knowledge base that has allowed him to mentor others as they build hemp-based products. He is grounded, knowing this is a long journey and a lifestyle change. And, he is playing his part to educate everyone that hemp fiber is a part of creating a better future for the planet and has a place in manufacturing textiles in the United States.”

One person who benefited from Carpenter’s willingness to mentor is Claire Crunk, founder and CEO of Trace Femcare Inc., a period care company that produces tampons using hemp and cotton fibers from fully traceable sources. “When I got my start in hemp fiber almost five years ago, I was a total neophyte,” Crunk said. “When I cold called Guy, he was gracious and clearly an expert, so right then and there, I asked him to be my mentor. Guy has been a consistent and selfless mentor since then — teaching, encouraging, and providing more than any conference or curricula ever could. He is one of our company’s most important partners, and I admire him both professionally and personally and am privileged to now call him a colleague and friend.

“As one of the first brands to sell products made from U.S.-produced textile-grade hemp fiber, we are proud that our work ultimately supports our partners, like Guy, in their success to provide textile industry quality hemp fiber at scale.”

Vans: Mainstream Interest In Sustainable Fibers Like Hemp

Brands are taking an interest in hemp too. VF Corp. believes “hemp has the potential of filling in some of the gaps in our fiber toolkit for brands and products that would like to utilize more natural fibers.”

“VF recently set ambitious goals for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions utilizing science-based targets, and as one of VF’s largest brands, Vans is committed to supporting these goals,” said Emily Alati, director, Materials Innovation, Vans. “We believe supply chain innovations in natural fibers, including hemp, are necessary and if cultivated with sustainable agricultural methods and processed with lower energy inputs, it can be a competitive advantage to help VF reach those goals.”

According to the company, Vans has used hemp in its products for years, so supporting U.S. hemp agriculture and textile processing also aligns with its consumer and supply chain needs. Vans is currently sourcing hemp fiber from North Carolina in small quantities and hopes to increase that volume over time.

“We are also supporting those hemp farmers in their transition to regenerative agriculture practices to reduce the overall environmental impact of hemp farming,” Alati said. “Ultimately, we are eager to utilize regeneratively grown and U.S. hemp fiber while supporting minority farmers. Long term, we hope to see all VF brands utilizing domestic industrial hemp fiber and textiles for various end-uses across our global markets.”

Vans’ collaboration with Bear Fiber benefits both companies. “The relationship is based on expertise, trust and results,” Alati said. “Bear Fiber has demonstrated that hemp fiber suitable for short staple spinning can be grown and processed entirely in the United States. Its relationships with textile universities, labs and processing partners have led to commercial textiles in a relatively short time span.”

For Bear Fiber, the support received from VF Corp. and Vans starting some two-and-a-half years ago has been incredibly important. “You have a lot more credibility when you walk into a room with people employed by one of the most important brand companies in the world who say ‘we are behind hemp, we think hemp is important and we think this is the future,’” he stressed.

Bear Fiber currently is producing fabric for Vans. The yarn is spun by National Spinning Co. Inc. at its Whiteville, N.C., plant; the fabric is woven by Central Textiles Inc., Central, S.C.; and finishing is performed by Mount Vernon Mills Inc., at its facility in Trion, Ga.

BFFs: Hemp And Cotton

Hemp is also seen as a potential competitor to cotton, which at times, hampers adoption of the plant for farming and textile use. Carpenter wants to stress that he doesn’t see hemp as a competitor or replacement for cotton and just wants to sell the value of another fiber crop. He sees the two as complementary fibers — best fiber friends (BFFs) — that can help both the farmer and the textile industry. “We are not asking farmers to grow hemp instead of cotton,” he noted. “We are asking them to grow it along with cotton.

“We want to replace 50/50 cotton/polyester blends with 65-percent cotton/35-percent hemp,” Carpenter continued. “We export our cotton everywhere because it’s of the highest quality. One day I hope to be exporting U.S. hemp fiber because it’s sought after for its quality. And the opportunity for hemp blended with U.S. cotton is tremendous.”

Carpenter considers Bear Fiber’s perseverance its greatest asset. “We know yarns and fabrics can be made to meet the quality standards that the brands and consumers are looking for because we’ve been doing it for 25 years in China.”

Ultimately, Carpenter wants what is best for the U.S. fiber industry and the U.S. textile industry.

“I want to help grow the hemp fiber industry into the American textile, apparel and fashion industries,” Carpenter said. “I think an American hemp fiber industry not only can provide consumers with better garments that last longer and feel better but can also be a huge benefit to small farmers and fiber farmers who are already growing cotton.

“The only competition we have is China, and we’re going to be better than them,” Carpenter predicted. “Consumers today have a heightened awareness of natural fibers and sustainability, and are demanding better choices. It’s up to the U.S. textile manufacturing industry to take advantage of this opportunity, to innovate and promote from the ground up our own domestic value chain. In the United States, we’ve already got the best cotton in the world, and that’s a huge advantage. But you know what? Hemp makes it better!”

November/December 2022