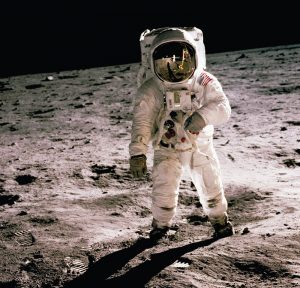

large role in allowing man to walk on the moon and beyond. By necessity, textile performance also has evolved.

(photo: History in HD)

As time and technologies progress, the definition of a textile’s performance will also continue to evolve.

By Jim Kaufmann, Contributing Editor

In the grand scheme of things, it really wasn’t so long ago that the term “performance,” as specifically related to textiles, consisted of two rather basic questions — does it keep a wearer warm or cool depending on the time of year? And how long will it last until I need to replace it? Not long after, a notable refinement occurred, and the two original questions evolved into a new basic three: Does it work? — a combination of the original two questions; Can I get it?; and lest we forget the all-important question, How much does it cost?

Inevitably, it was decided that different colors were a good thing and making sure that colors could be produced in a repeatable manner was added to the growing list of performance attributes. As the textile industry continued to advance and became more technically adept using not only cotton and wool but also newly developed man-made fibers, technologies improved and new attributes added further definition to products. Fabric forming technologies became defined as the big three — weaving, knitting and nonwovens. Refinement of characteristics such as construction, pattern design, weight, tensile strength, elongation, and other properties became common place for manufacturers in order to better quantify products, while also helping to improve quality and consistency.

Fast forward again to when engineers realized that textiles could be used in areas other than clothing or linens. As a result, industrial textiles become more clearly defined, though still largely unrecognized to much of the general public. High-performance fibers — including Nomex®, Kevlar® and spandex, among other fibers —were developed, along with a variety of coatings and laminated options.Performance definitions expanded to include flame retardancy, air permeability and water permeability. Not to be outdone, the traditional textile industry became much better at creating or designing for seasons, climate characteristics and comfort levels. New methods of defining textiles using terms such as drapability, washability, colorfastness, and abrasion testing along proper documentation, specifications and certifications became commonplace.

In the present day, the word textile ostensibly continues to be associated with negative historical connotations. The nonwovens segment appears to have distanced itself from textiles altogether and increasingly textile is being supplanted by terms such as performance fabrics, engineered materials and fibrous composites —or it’s just not mentioned at all. The characterization of performance continues as the list of attributes expands becoming increasingly more comprehensive as does our collective knowledge of products and technologies across the board. Several recently coined terms or phrases including sustainability, product transparency, recycled content, circularity and social responsibility have now taken center stage in textiles and other related industries, which represent a whole host of new issues emanating from growing environmental, health and societal concerns.

Traditional Plus “New” Performance Criteria

Sustainability has become a rather complex concept as it relates to the textile industry, yet it is simply defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “the ability to be maintained at a certain rate or level.” However, according to the website youmatter.world in its “Sustainability — What Is It? Definition, Principles and Examples” article, in recent years: “because of the environmental and social problems societies around the world are facing, sustainability has been increasingly used in a specific way. Nowadays, sustainability is usually defined as the processes and actions through which humankind avoids the depletion of natural resources, in order to keep an ecological balance that doesn’t allow the quality of life in modern societies to decrease.”

Product transparency, as the term implies, denotes the open disclosure of detailed information specific to the content and origins of products and any inputs used to create them. The term is becoming more visible and prevalent in many market segments. Social responsibility represents the efforts made to educate and entice businesses, professionals and consumers in taking a more active stance towards ensuring that today’s products purchased, the places where people live and work, or activities we all pursue are not a detriment to our personal health and/or the environment we inhabit.

Collectively, these issues are quickly rising to the forefront of many different textile industry segments. As a result, there has been a complete rethink of how performance is defined because “We’ve now reached a stage where traditional product attributes no longer provide enough information to tell the whole story,” noted Joe Walkuski, president of Boseman, Mon.-based Texbase Inc., during a recent joint workshop presentation with Ben Galphin, founder of Outsider Innovation, Charlotte, N.C.

During their presentation, Galphin and Walkuski pieced together and defended their view of what performance attributes for many textile products either have already expanded to include or likely will expand to include. To the more common or traditional textile performance attributes, Walkuski and Galphin added three equally important new segments — traceability, utility, and the aforementioned sustainability.

Traceability highlights the growing and extended responsibilities being progressively demanded by consumers and increasingly legislated by governments of textile brands and their manufacturers to defend the authenticity of supply chains, the inputs used and resultant products produced. Traceability also encompasses an increased need for verification of environmental and social good. For example, is there verification that the products are being manufactured in a societally ethical and safe environment and the inputs used are validated to be what the specification says they are? Regulation of potentially harmful chemicals, reduction in counterfeiting and possible manufacturer liabilities are also considered within this segment. “We have seen an increase in testing requests from customers who want to verify and confirm that what they received is actually what they intended to purchase,” reports Katrina Penegar, testing lab manager for the Textile Technology Center at Gaston College, Belmont, N.C.

As technical knowledge and capabilities increase, the utility of everyday fabrics in virtually all market sectors are also increased, adding to a performance rethink. Growing technologies contributing to this rethink include antimicrobial and antiviral ingredients or finishes, active insect protection from tick and mosquito-borne dis-eases, drug- or vitamin-infused yarns and fabrics, effective thermoregulation from sun exposure, and protection from increasingly severe weather events, among other technologies. The advent of smart textiles is creating further utility in this realm as people become more accustomed to incorporating electronics in some form or another into their wearables or other more advanced technical applications. In addition to testing, validating and verifying the continued effectiveness of these and other technologies, consideration must also be given to ensuring that new testing methodologies or refinement of existing ones are following suit in order to accurately measure new aspects associated with performance.

Fundamentally, sustainability refers to doing more with less, but it has become an all-encompassing umbrella term that appears to have transcended products, markets and industries. From the textile perspective, Galphin and Walkuski effectively summarized sustainability as “carbon, fiber and social accounting.” Accounting in this instance is more about the details attributed to specific actions being taken. For example, what are we doing or what is still needed in order to reduce cabon footprints? How can we eliminate microfiber generation and fiber shedding as well as plastic waste globally? And of course, how do we become more socially aware of the impact of the actions we take or maybe do not take? Even increased consideration of the items we purchase and whether collectively our actions will lead towards a more sustainable environment should be taken into account.

Green Products

By all appearances, industries and individuals indeed are beginning to take action. “We’ve seen a big shift in interest towards making the world healthier,” Penegar said. “Everybody wants green products and natural fibers of all types are gaining in interest because consumers are realizing that they don’t want items that may end up in the ocean or a landfill, possibly for a few hundred years. But, unfortunately, not all green fabrics are actually green, so we test.”

Efforts are ongoing to reduce the use of potentially harmful chemicals in dyestuffs and other textile treatments. Several companies have recently announced that they either have, or will, eliminate the use of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly called PFAS or forever chemicals, from their products. The “reduce, reuse, recycle” movement continues to gain in popularity as does circularity, especially with younger generations as the environmental harm from waste streams is brought to light.

Impact Beyond Textiles

The initial focus of many of these efforts began with apparel, but similar efforts are being found in other industry segments as well. The commercial building industry, certainly in the United States and Europe, has noticeably increased its efforts, and possibly to a degree, confusion, stemming from the bevy of programs currently cited for many new commercial builds. These include, in no particular order, the Health Product Declaration Collaborative, the Living Future Institute, Cradle-to-Cradle, Clean Production Action, Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturers Association, Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED), International Well Building Institute’s WELL, and the Living Building Challenge (LBC), among other programs and certifications.

The LEED program is probably most recognizable currently with architects, builders and building owners, many of whom are intent on making every effort necessary to be awarded a coveted LEED rating for their buildings. LEED ratings are based on a series of credits or points achieved specific to how that building addresses segments such as climate change, impact on human health and water resources, and how it contributes to supporting biodiversity, a green economy, community and natural resources. The effective use of textiles in building construction can in many cases improve a LEED rating.

In a similar vein, the LBC has upped the ante of LEED by taking a more “holistic approach to building that requires all project stakeholders to consider the real-life cycle impact of design, construction and operation.” From a textile perspective, product transparency is a requirement, but where LEED provides credits for the use of recycled content, LBC goes further requiring that qualified buildings not use any materials, chemicals or elements that are found on its Red List. The list comprises items “known to pose serious risks to living creatures and the greater ecosystem that are prevalent in the building products industry.” The Red List is updated annually and represents the “worst in class” substances. It contains chemical names, trade names and synonyms, as well as chemical abstract service numbers to properly identify the items in question.

Of course, these ongoing and ever evolving activities will continue to be ongoing and ever evolving. As a result, the need to rethink performance and the attributes that define performance in textiles will continue to evolve as well. This ever-changing landscape offers job security for those who deal with the subject on a daily basis. That said, there is one attribute that hasn’t been mentioned since the very beginning of this adventure and is likely to remain the most critical factor — cost.

Unfortunately, sustainable production and virtually all of the aforementioned performance properties do not come free and, in many cases, can be costly! Walkuski and Galphin summed up their presentation by offering: “Sustainability, however you wish to define it, has effectively become the new performance! There is a very real cost associated with sustainability, not only the raw materials and manufacturing costs, but also the costs associated with developing viable solutions. There remains the very real question of worth versus risk versus company initiatives versus customer acceptance and everyone’s continually changing perceptions.”

The old profound truth that “one thing leads to another” seems rather appropriate as the ongoing challenge that every company — whether it be manufacturer or supplier, marketing agency, engineering firm or consultancy — either is facing or will soon be facing are the ultimate questions; What level of risk are they willing to absorb? And how do we actually pay for these efforts? This question includes the necessary work being done to not only rethink performance, but also define and monitor it. Ultimately, the answers may come down to how far is the consumer, as well as the companies involved, willing to go in order to realize the costs and absorb them in some manner or form? Performance, regardless of how it is defined, certainly brings value to those who strive for and appreciate it, but in the grand scheme of business, societal norms, various increasing environmental concerns and consumer sentiment, are we willing to accept the risk or somehow collectively able to pay for it? One certainly hopes so!

March/April 2023