Centuries-old Johnstons of Elgin keeps the cashmere flag flying high in Hawick.

Dr. Andre West, Technical Editor

William Lee was an English clergyman and inventor who devised the first stocking frame in 1589. The fundamental principle of knitting on this machine remains the same to this day, and his design was not improved upon for some two hundred years. Lee’s first machine produced a coarse wool stocking — unfortunately not the finery of silk that could be knitted by hand. Legend has it that Queen Elizabeth I refused Lee a patent on the basis that the machine would kill industry, and said: “Thou aimest high, Master Lee. Consider thou what the invention could do to my poor subjects. It would assuredly bring to them ruin by depriving them of employment, thus making them beggars.”

Hawick: A Traditional Textile Town

Hawick — pronounced Hoyk by the locals — is a town in the Scottish Borders is known for its centuries-long traditions, one of which is knitting. James Hardie introduced the stocking-frame to Hawick in 1771. In 1791, there were 12 frames in Hawick that employed 14 men and 51 women. The introduction of this new technology into mills was not without its consequences. In 1779, Ned Ludd destroyed two stocking frames in England. His name — and the word Luddite — has become synonymous with any movement opposed to increasing industrialization, or new technology resulting in a reduced labor force while increasing production. In reaction, Parliament introduced “The Destruction of Stocking Frames Act of 1812” making the destruction of mechanized stocking frames a capital felony punishable by death. With this new law in place, by 1844 there were 2,605 knitting frames in Scotland, the majority found in Hawick.

By the mid-19th century, Hawick companies had moved beyond stockings to producing all types of knitted undergarments. In the late 19th century, finer raw materials, such as cashmere, was imported, which established Hawick as the cashmere capital of the world for almost 200 years. Companies including Hawick Cashmere, Hawick Knitwear, Johnstons of Elgin, Lyle & Scott, Peter Scott Pringle of Scotland, Scott and Charters, and George Woodcock & Sons all have had, and in some cases still have, manufacturing plants in Hawick, producing some of the most luxurious cashmere and merino wool knitwear known in the world today.

Johnstons Of Elgin

Johnstons Of Elgin

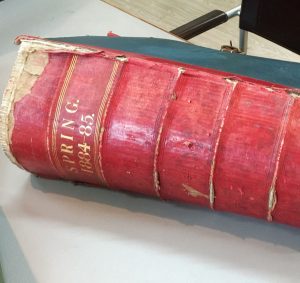

While industrial knitting was establishing itself in the Scottish Borders, 225 miles north of Hawick in a town called Elgin, a woollen mill was opened in 1797 by two families — the Johnstons and the Harrisons — called Johnstons of Elgin. They established a plant that still is in production today.

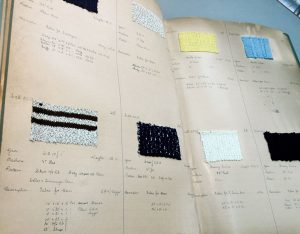

Originally, Johnstons produced linen, flax, oatmeal and tobacco. After the introduction of textiles, the non-textile products were phased out. Johnston pioneered the use of tweed for camouflage, and the style became known as Scottish estate tweeds. Wool was first referred to in the Johnstons of Elgin records in 1801 and has continued to be a key raw material for the company. Johnstons is the only manufacturer that goes from raw material through every stage of the manufacturing process — including spinning, dyeing, and weaving or knitting — to finished products on one site, thus making it the only vertical mill in Scotland.

Over the years as its business has expanded, Johnstons has endeavored to build a community, one that it professes is the company’s greatest asset. Johnstons has been one of the largest independent employers in the Elgin area since the mid-1800s. Currently, the company employs just over 1,000 people.

Its more than 200 years of expertise in textile manufacturing and sourcing only the finest raw fibers available allows Johnstons to lead the world in luxury cashmere and woolens supplying the world’s top fashion luxury brands. Cashmere is one of the finest, most luxurious natural fibers in the world renowned for its extreme softness, warmth and lustrous quality. The dramatic fluctuation in temperature throughout the year — rising to above 40°C in summer and dropping to below 40°C in winter — helps the goats to grow their beautiful, downy under-fleece. The natural crimp of cashmere fibers helps them to interlock during manufacturing and allows the fibers to be spun into very fine, lightweight fabrics. This is where Johnstons’ cashmere sets itself apart said David Hamilton, operations director. “There are in the region of 30 different processes involved in transforming raw fiber into luxurious products,” Hamilton said. Each evening, the tail of the day’s finished fabric is laid out for Hamilton to inspect as he is leaving. He strokes each fabric and gives his seal of approval by flipping the end back into the barrel as if he has just blended the perfect whiskey.

“The contemporary Johnstons of Elgin mill uses cashmere blended from fibers carefully selected from Mongolia, China and Afghanistan; and lambswool from Australia,” Hamilton said. “Combining the different qualities of these fibers to optimize the performance of the fabrics, allows Johnstons to provide the best combination of durability, hand and feel of any given product.”

Most of the cashmere the company uses is gathered from approximately 1 million goats, which are herded in the traditional ways used for hundreds of years. This unique lifestyle helps to preserve these fragile communities. Although working directly with herders and farmers is difficult, Johnstons collaborates as a founding member of the Sustainable Fiber Alliance to develop sustainability programs to improve the situation for both goats and herder communities.

Fully Fashioned Garments

In the 1970s, the company expanded its knitwear operation to Hawick as the town had grown to be historically known for cashmere knitwear and skilled craftsmen. Some of Johnstons’ knitwear is fully fashioned — meaning that each garment is knit to shape to give the best fit — on older Bentley-Cotton full fashioned frame machines. The ribbed trimmings, cuffs, collars, welts, pockets and straps first are knitted on separate machines. These are then transferred onto the frames that knit the fronts, backs and sleeves to complete the garment. The garments are carefully washed and milled, before the final step where collars are linked to the garment, and buttons, buttonholes and trims are added — many by hand.

In recent years, Johnstons has invested in the most advanced WholeGarment equipment from Japan-based Shima Seiki Mfg. Ltd. The latest Shima machines installed at Johnstons allow the machine to take much of this very labor intensive assembly process away by knitting the majority, if not all of the garment, on the machine to the exact size thereby eliminating the need to sew the garment.

The Hawick facility knits sweaters, cashmere hats, scarves, accessories and gloves on a modern Shima Seiki SWG041mini. The company also recently invested in Shima’s flagship machine — the 4 Bed Mach 2XS WholeGarment machines.

However, what has not changed at Johnstons over the years is the professional devoted craftspeople — some of whom have been honing their skills for almost 50 years. The experience and tradition rooted in their history have been passed down through generations to ensure they are preserved and represented in the timeless pieces made today. Central to supporting and developing its legacy is Johnstons’ own training center in Hawick that offers apprenticeships to locals concerned with the preservation of traditional crafts. The company is doing its utmost to ensure the conservation of these increasingly rare skills.

It would be a crime not to use each and every ounce of cashmere into a crafted piece of fabric. This has become difficult with today’s fashion trends and colors turning quicker than the local salmon in the global industry. Johnstons devised a plan to process the batch ends of fibers, yarns and cut-offs, which are reused and redyed to produce scarves and other products. Each piece features materials available at the time of making so every product is unique and makes a beautiful gift worth countless hours of effort and care.

Traditions Run Deep

When touring the plant, one gets a sense the employees feel blessed to carry the traditions of their ancestors forward. They have no choice but to produce the perfect garment every time. The mill does not close for any unofficial holidays except one — the yearly Hawick Common-Riding festival. The event commemorates horse riding of the boundaries of the Border towns’ common land, victory over the English army in 1514 and — most importantly — capturing the flag. The event, sponsored in part by Johnstons, starts with the election of that year’s principal man — known as the Cornet — in the spring, who is chosen from among the community’s young established men. The flag is then given to the Cornet, who is reminded that the flag is “the embodiment of all the traditions that are our glorious heritage.” The Cornet is charged to ride the marches of the community of Hawick and return the flag “unsullied and unstained.” Rides today involve hundreds of horses culminating in the town’s center where hundreds of locals, many of them Johnstons employees, crowd the sidewalks to cheer the riders as they pass through.

It is well-known in the 21st century that technology and progress cannot be stopped like Queen Elizabeth I and Ludd may have wished. Manufacturing traditions run deep in Scotland. However, these traditions do not stop investment in technology that keeps Johnstons at the forefront of fashion even after all these years in business. The company has embraced manufacturing challenges just as the established youth of its town are asked to do each year at the Common-Riding festival.

September/October 2016